MUSIC 246 - Soundtracks: Music in films

Simon Wood

Estimated reading time: 23 minutes

Table of contents

Lecture 1

Part A: Welcome To The Show!

This course is about music and movies and what happened when they put together.

Textbook is like Google Earth view. Listening to lectures is like Google street view.

And I’ll see you again in Part B.

Part B: Our First Scene

This is the music written specifically for the scene. The film has already been chopped and the composer was writing music while watching the film on fold. The composer has synchronized the music they have written to what goes on within the scene. Watch the scene with the sound off. Then listen to the music with the sound on. VIDEO EXAMPLE 1-Apollo 13.

🎥 video playing 🎥

The first part shows the wife of one of the astronauts in a hotel. She is nervous cause her husband is going to the moon. She’s scared that he’s never come back. While she’s in the shower, the wedding ring slides off her finger and goes down the drain. It manifests the wife’s fear of losing her husband. No music during shower scene. Why?

- Small, intimate scene. Music would risk over-dramatizing.

- Leave “space” for what follows. After this scene, music continues for several minutes through the launch scene.

Where music “isn’t” can be as important as where it is. Music fades in under shower scene – smoothes transitions.

- Instruments:

- Brass – military – heroism – sacrifice

- Synthesizer Bass - Technology

- Style: Chorale – Protestant Hymn – faith – sacrifice

- Tempo: Slow – restrained – controlled – professional

- Change in musical texture with transition to external scene.

Part C: The Four Functions

Now let’s take a look at an example of how music can alter perceptions of things. Mrs Doubtfire: Original Trailer; Fake horror trailer.

Any visual image, and put any piece of music on it, sth will happen. This will vary from viewer to viewer, listener to listener, depending on the background. But usually, when director and composer sit down and decide on what the music is going to do within the context of a particular film, they want the audience to notice/feel some particular things.

What is a movie? What is a film? Why is there the music in the first place? We are going to focus on the most common, generally, narrative film: tells a story, in a coherent, consistent manner.

Suspension of disbelief. Like a contract between the audience and the film makers. It says: Ok director, I gonna accept what you show is real. The one thing that film maker cannot do is drawing attention to the fact that what you are watching isn’t real. For example, inconsistency between scenes. Avoid all these things and present the audience a world that is believable, consistent, real. Then, over the top of it, we have music. We don’t have music in real life. It would be nice if we have music IRL: it will tell us when we will have trouble or succeed in some situations. And yet, we got music all over the films. So shouldn’t music be like those continuity errors (inconsistency)? It’s something telling us the people in the film world can’t hear the music, but we can, which is artificial. Music does become a very common part of film making. So why is it there?

The Four Functions

- Music can create a more convincing atmosphere of time and place.

- historical, cultural, geographical – BUT based on western conventions.

- Music can underline or create psychological refinements.

- the unspoken thoughts of a character or the unseen implications of a situation.

- Music can provide a sense of continuity in a film.

- structure of music “smoothes over” the discontinuous, chaotic nature of film.

- Music can provide the underpinning for the theatrical buildup of a scene and then round it off with a sense of finality.

- music can affect the “pacing” of a scene.

Lecture 2

EVALUATING A SCORE: How do we talk about what we hear?

Diegesis (叙事): The world of the narrative. All characters, events, etc depicted, suggested, or described.

Diegetic Music: 画内音

- music whose source is within the Diegesis.

- heard both by the characters within the narrative and the film audience.

- also known as “source music,” “direct music,” or “foreground music.”

- Functions include: establishing time and place, creating a sense of “realism and immediacy,” offering ironic comment.

Nondiegetic Music: 画外音

- heard by the film audience only.

- Referred to as the “score,” “underscore,” or “background music”.

- Normally originally composed for the specific film (original score).

- May also included preexisting music “adapted” for the film.

Difference between score and sound track. Score: music written specifically for accompanying the film, usually written after the film is shot. Sound track: collection of preexisting popular songs.

An example of adapting music: The Sting (1973) Music of Scott Joplin, adapted by Marvin Hamlisch.

May also include preexisting music used without adaption, Example: Platoon (1986) Composer: George Deleure, also includes Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings (1938). Also used in The Elephant Man (1980) and Sicko (2007).

Example: Platoon (1986) Using the “Adagio For Strings” by Samuel Barber

All preexisting music, “Compiled Score.” is all music in the score are preexisting music without alteration. Such as the music used in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Compiled from the works of R. Strauss, J Strauss, etc …

Now we describe the music.

Style

- what type of music has the composer chosen?

- what type of instruments?

- how do these choices relate to the film as a whole?

Restoration (1995) Composer: James Newton Howard

- set in the mid 1600s.

- Score is part original part adapted, based on the work of Henry Purcell, an important composer of the period.

- Use of period instruments including Harpsichord.

- Example: Restoration (1995) Music by James Newton Howard, based on a theme by Henry Purcell

Local Hero (1983) Composer: Mark Knopfler.

- plot follows an urban American in a small Scottish village.

- blend of folk and popular styles.

- emphasis on instruments such as the guitar.

- Knopfler developed melodies similar to Anglo Celtic folk music

- Example: Local Hero (1983) Music by Mark Knopfler

The Godfather (1972) Composer: Nino Rota

- follows the life of an organized crime family.

- much of the instrumentation and melodies based on the folk music of Sicily.

- solo brass, not military, not heroic, sounds mournful, tragic, alone.

Concept

- is the music used in a consistent manner throughout the film?

- What is accompanied? What is left without accompaniment?

- What “motivates” the music? Action, characters, events, objects, flashbacks, etc…

Conceptual Approaches: Most film music will fall somewhere between two extremes:

- Playing the Drama

- music attempts to reinforce primarily emotional elements within the narrative.

- Hitting the Action

- music accents visual events: car chases and so on.

- common approach to cartoon scoring.

- “Mickey Mousing”.

Musical Characteristics

Melody or Theme

- Considered the most “recognizable” music element for western ears.

- Do characters, objects or situations have a particular melody associated with them?

- German Opera composer Richard Wagner – Leitmotive.

- Melodies can be taken through a number of variations to tell you what is going on within a particular character – thoughts or feelings etc…

- Are the melodies easy to hum, or are they “angular” and more difficult? If a melody is associated with sth positive within the film world, then it would be a bit easier to hum, smoother. More angular, harder, then on the dangerous/less desirable side. This “rule” is quite generalized…

Tempo or Pulse: how fast does the music unfold, how quick is the beat?

- How does the speed of the music influence the “tempo” of the narrative?

- On-screen action, framing, editing, sound design.

Example: The Return of the King (2004) Composer: Howard Shore

🎥 video playing 🎥

Harmony: vertically

- Difficult to describe without musical training.

- Consonant or dissonant? Orderly or Chaotic?

- The major / minor scale.

Examples:

- Highly Consonant: Main Theme from Cider House Rules (1999) Composer: Rachael Portman

- Blend of Consonant and Dissonant: Yes from Meet Joe Black (1998) Composer: Thomas Newman

- Dissonant: Bishop’s Countdown from Aliens (1986) Composer: James Horner

Lecture 3

Technical Details, How It’s Done

Basic Timetable

of Film Production

- Preproduction: planning phase, preparation: script / financing / casting / costume and set design / location scouting

- Production:

- finalization of script and production design

- principle photography (主体拍摄): filming the actors, shooting various scenes.

- Postproduction:

- assembling and editing the “takes”

- completion and addition of visual and audio effects

- composition and addition of music

- normally, an original film score is one of the final elements to be created and added to the film.

- historically, schedule for the composition and recording of a score: 5 to 8 weeks on average. Although often still the case, effects-driven films often have longer post-production periods.

Composer’s involvement varies based on working style and specifics of a given project.

Scripts: - can give composers a “head-start” - research for “ethnic” or “historical” influences. Example: Hans Zimmer; The Last Samuri (2003) - production of important source music is done at this point - in general, composing the score cannot be done on the basis of a script – why? - scripts can change significantly - only words, no clear timing or pace for the composer to work with.

Screenings: - several different opportunities to see the film - rushes: film shot that day - assembly cut: significantly longer than finished film - rough cut: closer to finished film, but still undergoing significant editing - fine or locked cut: most if not all editing completed. This is what the composer is really waiting for, because rough cut might not be accurate in time. Basic timings will not change. - most composers begin serious work at the fine cut phase - concern that repeated viewings will alter the composer’s reaction - timing of scenes

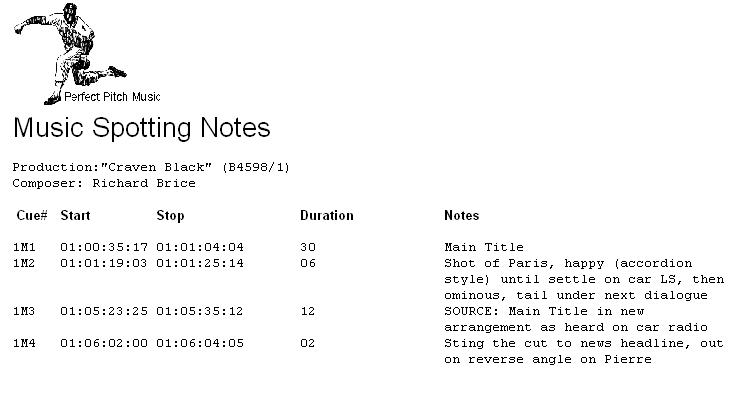

Spotting Session and Cue Sheets: director, composer, music editor/music supervisor sit together, watch the films, discuss the placement of music, style of music. Music editor takes careful notes, produces a “cue sheet”/”spotting notes”. Cue: piece of music in the film. For example, music for the fight scene is a cue. In the cue sheet, we have cue number. Final category, notes, description for what the music is for, where the music goes.

Pic from https://soundclass.weebly.com/6-spotting-for-sound-design.html

- “temporary” music added to film while still in production or early editing.

- gives more “finished” feeling to work in progress.

- often taken from other film scores, or “classical” music.

Composers are deeply divided on their view of temp tracks

- offer insight into director’s thinking process.

- BUT can influence the composer’s initial response.

- director’s familiarity with temp track can be an obstacle.

Composing:

- 5 to 8 weeks until “delivery” of finished score

- short timeline due to fixed release date

- frequently exacerbated by production phase running overtime

Generally, composers don’t have time to write every note for every individual instruments. So they have orchestrators to help them – skilled in composition, music theory, and knowledge of the orchestra. Before going to the studio recording, we have synthesizer demonstrations. Send a paper with all different instruments written on one page to copyist, who produces final individual parts for musicians. Music librarians organize parts for recording sessions. Finally, we get conductors and studio musicians (good sight readers).

Examples: Thomas Newman – Wall-E. John Williams – The Phantom Menace

Western Classical Music History

Check music 254, music 255, music 256.

Baroque Period (1600-1750)

- Key Composers: Vivaldi, Handel, Bach.

- Development of “Common Practice” – major/minor system of music theory.

- Musical structures most important.

- Even tempos, consistent textures, terraced dynamics.

- Example: J.S. Bach, “Brandenburg Concerto No. 6” 3rd Movement (1721)

Classical Period (1730-1820)

- Key Composers: Mozart, Hayden, Beethoven.

- Greater focus on melody and emotion.

- Expanding variety of tempo, texture and dynamics.

- Example: W.A. Mozart, “Symphony No. 40” 1st Movement. (1788)

Romantic Period (1800-1910)

- Key Composers: Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Strauss.

- Expression of emotion was most important.

- Even greater range of tempo, texture and dynamics in service of emotion and narrative.

- Example: R. Wagner, “The Magic Fire Music” from Die Walkure (1870)

1870 is only 25 years away from the birth of motion pictures. Not surprisingly, all composers in film industry have grown up listening to people like Wagner. Indeed the birth of film music.

Melodramas. In modern usage, a melodrama is a dramatic work wherein the plot, which is typically sensational and designed to appeal strongly to the emotions, takes precedence over detailed characterization (from wiki). It has a lot of music, quite unlike plays. Like early version of accompaniment for narrative film.

The Silent Era

1895 - 1927

The Persistence of Vision. See the detailed treatment on wiki. We can see continuous images. One toy: The Zoopraxiscope (1879) – project several images to present the illusion of movement.

Thomas Edison:

- The Kinetoscope (1891) Peephole viewer with a continuous loop of film. No sound.

- The Kinetophone (1895) A kinetoscope with a phonograph installed in the box.

- Problem with synchronization: the current technology does not line up the sound and visual image. So recording would be appropriate.

First Projected Films: The Lumiere Brothers, Paris December 28th, 1895. “The Arrival of a Train”

Reasons for musical accompaniment:

- Pragmatic: mechanical noise / mechanical problems

- Psychoanalytic: Audience disturbed by ghost like images

- Continuity of Tradition: Long history of musical accompaniment for visual presentation.

During the Silent Era: Three general approaches to music: originally composed, adaptations of classical music, arrangements of popular songs.

Venues: Vaudeville Theatres. Live variety shows played in theatres. In the intermission, photoplays: short fragment in real life like one from the Lumiere Brothers. When the photoplays are on. Musical accompaniment provided by vaudeville orchestra: accompany for the show, and continue playing for the photoplays. Very quickly, photoplays became the most popular part.

1905 “Nickelodeons”, solely showed the movie. Music provided by piano, player piano, small ensemble or gramophone. Rarely the music has anything to do with the thing on screen. It’s very popular. 1907 – 3,000; 1910 – Over 10,000.

The Shift To Narrative

George Melies: early experimenter with camera effects, A Trip to the Moon (1902), Not the first narrative, but over ten minutes in length, multiple scenes, sets, costumes etc. early model for narrative film to come. This youtube link is colored, but colored movies didn’t exist yet. George Méliès has a team, primarily women, who hand-paint each frame.

1905-1910:

- Narrative films become most important element - films become longer - plots become more complex.

- Change in musical aesthetic from entertaining the audience to “playing the picture.” Music can support the drama and helping the audience to follow the plot. “Fitting” the picture or “Synchronizing”: align the music up.

1910 – 1920s: film industry matures. The rise of Hollywood. Films become longer, more sophisticated. First of the “Movie Palaces” built, 1912. Larger Orchestras (under the stage, orchestra pit like opera) and Theatre Organs: massive electric organ, many sound effects.

Some early attempts at creating original scores, but standard practice is either compilation of classical or popular music, or improvisation. 1909 – First attempt at “standardizing” musical accompaniment: Edison Film Company releases “musical suggestions” with each film. These were the first “Cue Sheets” with general scene-by-scene suggestions for musical accompaniment. In 1912, Max Winkler (Carl Fischer Music) suggests specific pieces of music, with timings. Films would be shipped with the cue sheets, might also include music. But problems with parts getting lost, lots of musicians involved might not like/know the pieces suggested etc. Thus this not work quite well.

Sam Fox Moving Picture Music (Vol 1, 1913) J.S.Zamenik. Contain contents, which suggests music for particular scenes. Music for Duels, music for storms. This hopefully makes it more consistent from theatres to theatres.

Trade papers: Motion Picture World, Moving Picture World

- articles and columns on musical accompaniment

- musical accompaniment should be continuous. Once the film starts, music should play all way through.

- source music. For example, if the scene is dancing, the band should play appropriate music like waltz.

- use of themes. How theme can represent a character or setting. Thematic transformation and letimotive from Wagner.

- “good music” (classical music) to the masses

By mid 1920s – no real change:

- vast range of performing forces and skills

- rural (local piano teachers/record players) or urban (see (semi)professional musicians playing music)

- missing cue sheets and scores

- issues of “control”

- thus completely not standardized

An example: Birth of a Nation (1915). Composer/Adaptor: Joseph Carl Breil

- remarkable influential film, becomes the norm of Hollywood films for decades in various aspects. Financial success. It is horribly racist even in 1915, huge controversy. About civil war.

- D.W Griffith: Hollywood’s first “great” director

- Carli Elinor – a music “fitter”

- Breil, American born, European trained musician and composer

- assembles a continuous score 2/3s similar to Elinor, but 1/3 original material written for the film.

- Debut in March of 1915

EXAMPLE ONE: Small ensemble of strings, woodwinds, brass and piano (Start 33:00)

EXAMPLE TWO: Big orchestra (Start 32:00)

First, two completely different music to the same scene result in different perceptions. Second, if in local theatre, both accompaniment would be exceptionally good for the time.

EXAMPLE THREE: The really painful example… (Start 29:30)

This was the problem: music can be powerful for the film presentation, help the audience interpret the film. No conceivable way to standardize the musical performance. So someone must come up with a way to record the sound and visual together, and play them back.

Lecture 4

Transition to Sound

Solution to the problems of musical accompaniment – recorded and synchronized sound.

In fact, almost a decade for the transition, late 1920s, early 1930s, sound and silent films existed together. Why big time lag? Economics. Expansive for the equipment, small theatres can’t afford. It may be weird that there were a lot of people who didn’t like sound films, sound films were a fad, novelty, they didn’t get used to it. 1920s, driven by progress in recording technology. Demonstrations of sound films as early as 1922.

Several competing systems emerge - the two primary approaches are:

- Sound On Film (Phonofilm, Movietone). Photograph of sound waves on the edge of the film

- excellent synchronization. Because both the visual image and the sound were being recorded on the single piece of media, the film strip.

- poor audio quality. 1920s, new experimental way of recording sound.

- Sound on Disk (Warner Brothers’ Vitaphone). The sound on giant records. By 1920s, records has been around for a couple of decades. Audio recording on a phonograph disk, synchronized with the film projector - excellent audio quality, poor synchronization. Vitaphone requites two devices, projector and record players. Also, disks are fragile.

As we moved to mid 1920s, Vitaphone became popular: the audio quality is much better. In 1926, Warner Bros releases a feature length motion picture: Don Juan.

- Recorded score primarily by William Axt, performed by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

- Vitaphone – recorded music and some generalized sound effects. No dialog, still a silent film.

- Also had a second score composed for “live” performance, because very few theatres have Vitaphone systems.

- Even though no recorded dialogue, still big hit.

The Jazz Singer (1927), first talking motion picture.

- primarily silent, with several minutes of synchronized sound through Vitaphone.

- most of the score is compiled or adapted.

🎥 video playing 🎥

Quite astonishing for the audience at that time. Big gap before the dialogue, and after, which is because the projectionist needs to switch the records. Also notice how stilted the dialogue is. No script writers, the actor is improvising, sound films do not exist. Barely no camera motion: cameras were noisy. Also, the actor cannot move very far because of the position of the mic. Moreover, the actor is not really playing the piano.

Thus still conventionally silent film. Nevertheless, a financial hit. It signaled the “beginning of the end” of the silent era. Sound on Disk has the early lead, but Sound on Film will become the standard by the early 1930s. Sound on Film has surpassed the audio quality of Vitaphone.

Now we enter the transition era, 1927 \(\to \) 1931 or 1932. Let’s talk about how the change to sound alters the approach to make motion pictures.

- Aesthetics. E.g., how does one act in the featured films. In silent films, one attempted to be overly dramatic with facial expressions or gestures, because no lines. Now they can say lines, so these old ways of acting look silly. Issue for industry: actors need to retool their acting skill. Another issue is the voices: decent voice is not necessary for silent films. In sound films, some of their voices are completely inappropriate. Also, a debate: Many worried about using none-diegetic music: “Where does the music come from?”

- Making films.

- all sound had to be recorded in real time. Postproduction does not happen straightaway.

- musicians on set – balance of sound music and dialog. When actor is playing, musicians have to play the music.

- cameras in large soundproof booths (because it is loud) – no movement.

- “sound stages” (expensive) are built to reduce/isolate outside noises

- Showing Films. Exhibition.

- Too many contesting sound systems. Vitaphone competes with sound on film system.

- Small number of the 20,000 theaters equipped for sound.

- end of 1929 almost 1000 theatres equipped for sound.

- by 1935 the transition is complete.

- See examples from Singin’ In The Rain which describes issues with filming and exhibition. (3/8) from Movieclips, (4/8)

- Industry Reorganization. The costs become higher for sound films so film industries are looking for ways to save money: All aspects of production are departmentalized – directors, actors, and musicians are put under contract – Leads to the STUDIO SYSTEM. Cost and control. Conglomeration: larger companies buy smaller. The “Big” Five: MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox (1935), and RKO. The “Little” 3 – Universal, Colombia, and United Artists. Both of them have bought everything they need to produce a film, but the “big” five owns distribution network and exhibition locations. Issue: monopoly when controlling all three: production, distribution, exhibition.

Max Steiner

1888 - 1971

- 1888: still at the end/height European romantic era

- born in Vienna (center of European classical music, the city of musicians), middle class, father owned a theatre

- formally trained in the tradition of European classical music.

- child prodigy – conducting in theatre by 12 – touring as a conductor by 16

- one of his teachers was Gustav Mahler

- wrote operettas, first by age 17

- also worked as composer and conductor of music for stage in England.

- facing deportation because of WWI Comes to US in 1914. In WWI, England was on one side, Austria was on the other and Max is Austrian.

He worked on Broadway for 15 years. In 1916 Steiner composes a score for a silent film (The Bondman) Invited to Hollywood in 1929, Rio Rita. Problems with actors’ voices - Hollywood turns to Broadway. Broadway is full of great actors with great voices. Recall many actors in Hollywood don’t have good voices, so Hollywood starts raiding Broadway for acting talent. Hollywood also needs to figure out how to write scripts. Then massive number of films are based on Broadway musicals. Broadway Melody is a successful film based on Broadway musical. On its poster: talking/singing/dancing. By 1930, little music in dramatic films – “where does it come from?” non-diegetic music will confuse the audience. Cimarron (1931) Score by Max Steiner. Quite a bit source music in the film. Innovative ways of approaching the music. David Selznick, producer at RKO recognized that more music might be good. (1932) Symphony of 6 Million, and Bird of Paradise. Continuous orchestral music, music well received by audience.

The turning point (1933): King Kong. Selling point, on the highest building. Early test audiences: The special effects look terrible, laughing instead of screaming. Still little music in the film. Afraid of losing money, the director convinced the studio to let Max Steiner write a lot of music. He wrote the score in 2 weeks. With his music this time, the audience screams.

VE4 King Kong – The Fog

🎥 video playing 🎥

between consonant and dissonant, mystery. Music used to indicate a transition from the normal world to the realm of the supernatural. Arrives at island, music shifts: view of the beach – Kong’s theme in an early distant form – lack of distinction between diegetic and none-diegetic music.

VE5 King Kong – The Dance

🎥 video playing 🎥

Music for the ceremonial dance uses a full orchestra, yet only drums are visible on film. Broadway influence to Max Steiner in this scene. Also, we see “mickey mousing” with the chief’s walk down the steps, tuba and low basses perfectly synchronized.

Another example of Max Steiner. VE6: The Informer – Opening

🎥 video playing 🎥

Folk-influenced theme for Gypo. Jazz-Influenced theme for Katie. Musical quotes – ‘Rule Britannia’. Won Academy award for “Best Original Score”.

Then he moved to Warner Brothers. 300+ film scores.